General information[]

Borchennymendi is the native language spoken by approximately 3,200,000 inhabitants of the Kingdom of Borchennymi, situated in the Atlantic Ocean, to the south of the Azores and to the west of the Canary Islands. The island country has been a constitutional monarchy since 1253. Its name means: 'mainland in the ocean', although it is never spoken of as 'Sealand'. Borchennymendi is a language isolate, featuring complex verbal constructions. Its orthography retained an archaic character, while its modern pronunciation is the result of a clearly phased development under the influence of the Portuguese tongue in the 15th and 16th centuries and the English language in the late 17th and early 18th, although Borchennymi was never colonized. A British attempt to do so in 1768 failed after 44 years, when the foreign oppressors were expelled after a short and rather peaceful insurrection in 1812. The Borchennymendi vocabulary shows some Latin influences as an effect of missionary activities from Gaul as early as the 5th century and from the British Isles in the 9th. A few words are derived from the Portuguese.

Phonology[]

Consonants[]

| Bilabial | Labio-dental | Dental | Alveolar | Post-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||||

| Plosive | p b | t d | |||||||

| Fricative | ϕ | f v | θ ð | s z | ʃ ʒ | ʁ | h ɦ | ||

| Affricate | |||||||||

| Approximant | ʋ | r | ɹ | j | w | ||||

|

Lateral fric. |

ɬ ɮ |

||||||||

|

Lateral app. |

l |

ʎ |

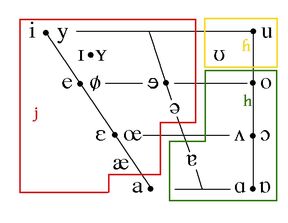

Vowels[]

| Front | Near-front | Central | Near-back | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close |

i y |

u | |||

|

Near-close |

ɪ ʏ |

ʊ |

|||

|

Close-mid |

e ø |

ɘ |

o | ||

|

Mid |

ə |

||||

|

Open-mid |

ɛ œ |

ʌ ɔ | |||

|

Near-open |

æ |

ɐ |

|||

|

Open |

a |

ɑ ɒ |

Alphabet[]

The alphabeth consists of only seventeen letters:

a b c d e g i (h only in digraphs) l m n o p r s t

Digraphs:æœ bh ch dh gh lh mh nh ph rh sh th

In books printed in Borchennymi h looks like ß, ſ is used for s except at the end of a syllable, q represents the digraph ch, and h at the end of a word looks like an undotted j. Uncial scripts and fonts are widely used. Capitals are not in use. There is only one punctuation mark (.) or (:).

Phonotactics[]

Although the syllable structure of Borchennymendi gives the impression of complexity, it is in fact very transparent. It allows the following possibilities:

|

- / V / - |

C / V / - |

CC / V / - |

CCC / V / - |

|

- / VV / - |

C / VV / - |

CC / VV / - |

CCC / VV / - |

|

- / VVV / - |

C / VVV / - |

CC / VVV / - |

CCC / VVV / - |

|

- / V / C |

C / V / C |

CC / V / C |

CCC / V / C |

|

- / VV / C |

C / VV / C |

CC / VV / C |

CCC / VV / C |

|

- / VVV / C |

C / VVV / C |

CC / VVV / C |

CCC / VVV / C |

|

- / V / CC |

C / V / CC |

CC / V / CC |

CCC / V / CC |

|

- / VV / CC |

C / VV / CC |

CC / VV / CC |

CCC / VV / CC |

|

- / VVV / CC |

C / VVV / CC |

CC / VVV / CC |

CCC / VVV / CC |

|

- / V / CCC |

C / V / CCC |

CC / V / CCC |

CCC / V / CCC |

|

- / VV / CCC |

C / VV / CCC |

CC / VV / CCC |

CCC / VV / CCC |

|

- / VVV / CCC |

C / VVV / CCC |

CC / VVV / CCC |

CCC / VVV / CCC |

V stands for vowel; C for consonant; - for none.

The seeming opacity is mainly caused by the written digraphs consisting of a vowel and h, which in fact is nothing more than a diacritic. They are regarded as one vowel in the pronunciation.

In the onset of a syllable Borchennymendi allows:

- no consonants, which implies the absence of an onset;

- one consonant: b, c, d, g, l, m, n, p, r, s, t and bh, ch, dh, gh, lh, mh, nh, ph, rh, sh, th;

- two consonants: bl, br, cl, cr, dr, gl, gr, pr, st, tl, tr; bhl, blh, brh, chl, chr, clh, crh, dhr, drh, ghl, ghr, glh, grh, phr, prh, shl, sht, slh, sth, thl, thr, tlh, trh and bhlh, bhrh, chlh, chrh, dhrh, ghlh, ghrh, phrh, shbh, shlh, shth, thlh, thrh.

- three consonants: str and shtr.

A vowel cannot be part of the syllable onset in the written language. The glottal stop is not a part of the consonant inventory and the spoken Borchennymendi shows a strong tendency to avoid it altogether. Words with an opening syllable as represented in the leftmost column of the table above are often preceded by a palatal approximant (j), a voiceless (h) or a voiced (ɦ) glottal fricative as indicated in the diagram. This does not apply to syllables of this type within a word.

The nucleus may encompass:

- one vowel: a, e, i, o, u, ae oe;

- two vowels: ai, ao, au, ea, ei, eo, eu, ia, ie, oa, oi, ua, ue, ui;

- three vowels: aou, eai, eoi, iai, iei, oai, uai.

In a three-vowel cluster only the one in the middle position is a genuine vowel. Both the first and the last are semivowels; the labiodental approximant (ʋ) in oai, uai and the palatal approximand (j) in eai, eoi, iai en iei.The only exception is aou, in which -ao- is a diphthong: aːw or the long open-back rounded: ɒː and u the semivowel ʋ.

No consonants are permissible in the nucleus.

In the coda three possibilities are allowed:

- no consonants, which implies the absence of a coda;

- one consonant: c d g l m n r s t and bh, ch, dh, gh, lh, mh, nh, ph, rh, sh;

( The consonantal digraphs ch, dh and gh are often (but not always) inaudible.)

- two consonants:

- ct, lb, ld, lt, mb, nd, nt, rd, rm, rn, rt, st,

- bhr, cht, cth, dhl, dhr, drh, ghl, ghm, ghr, ghs, ght, lbh, lch, ldh, lgh, lht, lmh, lth, mbh, mtg, mth, nbh, nch, ndh, ngh, nhd, nsh, nth, pht, rbh, rch, rdh, rgh, rhs, rht, rmh, rsh, rth, sht, sth, tch, trh,

- chrh, chth, dhrh, ghsh, ghth, lhth, mhbh, mhth, nhdh, nhgh, phth, rhmh, rhsh, rhth, shth, thch, thgh, thrh.

- three consonants:ntg, rtg, ghtg,

Over syllable boundaries the theoretical maximum length of a consonant cluster can be six positions (orthographically eight), but such a length is an extremely rare phenomenon. There are no radices that show it, so that it could appear only as a result of adding a suffix to a radix. The rule that no single vowel, vowel group, consonant or consonant group may be doubled often reduces the length of syllable clusters. If the application of this rule would obscure the meaning of a verbal of a nominal construction, a synonym for the radix is chosen from the extensive vocabulary. This is one of the main causes for the existence of irregular conjugations and declensions.

In the pronunciation the last consonant of a group of two generally becomes inaudible if it is written as bh, ch, dh, gh, lh and th at the end of a syllable followed by a syllable with a consonant or of consonant cluster in its onset.For instance: albh is pronounced as halʋ, but thalbhoir is: θaˈ.ʋoɹ.

Phonology[]

The Portuguese and English influences caused several and considerable changes in the pronunciation of medieval Borchennymendi. Before the 15th century it already lost all palatal, velar and uvular plosives and fricatives (except the uvular fricative often represented by rh in written texts). The velar plosives k and g were gradually replaced with lateral fricatives. The Portuguese merchants, who settled predominantly in the southern coastal regions, introduced the further nazalisation of vowels followed by the digraphs mh and nh. Influences from the English pronunciation may be seen in the elision of end-consonants like gh and dh and in the treatment of the dental fricatives th and dh, wich used to be aspired plosives.

Important characteristics of modern Borchennymendi are the modification of consonants by following vowels and the modification of vowels by subsequent consonants. The correct pronunciation, however, is fairly irregular and can be represented by the following tables, which are only indicative. Exceptions are as numerous as the rules.

The tables indicates the pronunciation of every possible VC combination within one syllable. The column on the rightmost side represents the modification of the original sound of c (k), when it precedes one of the combinations in the rows left of it. In the right column of each pair the regular pronunciation is indicated according to IPA.

Table 1[]

Vowels not modified by subsequent consonants.

| B | IPA | c | B | IPA | c | B | IPA | c | B | IPA | c | B | IPA | c | B | IPA | c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a |

a |

h |

ai |

i |

ɬ |

ao |

ɔ |

h |

au |

aw |

h | |||||||||||

|

æ |

æ |

ɬ |

æi |

iː |

ɬ |

|||||||||||||||||

|

e |

e |

ɬ |

ea |

ɪːɐ |

ɬ |

ei |

i |

ɬ |

eo |

ɪɐ |

ɬ |

eu |

ɛw |

ɬ | ||||||||

|

i |

i |

ɬ |

ia |

iːɐ |

ɬ |

ie |

iːə |

ɬ |

io |

ɪɐ |

ɬ |

|||||||||||

|

o |

ɔ |

h |

oa |

ʋa |

- |

oi |

i |

ɬ |

ou |

ow |

h | |||||||||||

|

œ |

ø |

ɬ |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

u |

u |

h |

ua |

wa |

- |

ue |

wɛ |

- |

ui |

iː |

ɬ |

Table 2

Modification of vowels by subsequent consonants and digraphs within syllables.

| B | IPA | B | IPA | B | IPA | B | IPA | B | IPA | B | IPA | c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ab |

ɑb |

abh |

ɑw |

ac |

ɑ |

ach |

ɑː |

ad |

ɑt |

h | |||||||

|

æb |

ɑːb |

æbh |

æːw |

æc |

æ |

æch |

æː |

æd |

æd |

ɬ | |||||||

|

aib |

ɛv |

aibh |

iːw |

aic |

ɪ |

aich |

iː |

aid |

iːd |

ɮ | |||||||

|

aobh |

ɔːw |

aoch |

ɔː |

aod |

ɔːt |

h | |||||||||||

|

aubh |

ɑːw |

auch |

ɑː |

aud |

ɑːt |

h | |||||||||||

|

eb |

ɪv |

ebh |

ɪw |

ec |

ə |

ech |

ɪ |

ed |

ɪd |

ɬ | |||||||

|

eab |

iv |

eabh |

ɪːw |

eac |

ɐ |

each |

ɪː |

ead |

ɪːd |

ɮ | |||||||

|

eaib |

iːb |

eaibh |

iːw |

eaic |

i |

eaich |

iː |

eaid |

iːd |

ɮ | |||||||

|

eibh |

iːw |

eich |

iː |

eid |

iːd |

ɮ | |||||||||||

|

eob |

œv |

eobh |

œw |

eoc |

ø |

eoch |

œ |

ɬ | |||||||||

|

eoibh |

iːw |

eoich |

iː |

ɮ | |||||||||||||

|

eubh |

œːw |

euch |

œː |

ɬ | |||||||||||||

|

ibh |

ɪ |

ich |

ɪ |

id |

ɪd |

ɬ | |||||||||||

|

iab |

ɪv |

iabh |

ɪw |

iac |

ʌ |

iach |

ɪ |

iad |

ɪd |

ɬ | |||||||

|

iaibh |

iːw |

iaic |

iː |

iaich |

iː |

iaid |

iːd |

ɮ | |||||||||

|

iech |

ɪ |

ɬ | |||||||||||||||

|

ieich |

iː |

ɮ | |||||||||||||||

|

ob |

ɒb |

obh |

ɒw |

och |

ɒ |

od |

ɒt |

h | |||||||||

|

oabh |

ʋɑːw |

oach |

ʋɑː |

oad |

ʋɑːt |

- | |||||||||||

|

oaibh |

ʋiːw |

- | |||||||||||||||

|

oaich |

ʊː |

h | |||||||||||||||

|

œbh |

ɛːw |

œch |

ɛː |

œd |

ɛːd |

ɬ | |||||||||||

|

oibh |

i:w |

oich |

iː |

ɮ | |||||||||||||

|

uch |

ʊ |

h | |||||||||||||||

|

uabh |

wɑw |

uach |

wɑː |

- | |||||||||||||

|

uaibh |

yːw |

uaich |

yː |

uaid |

yːd |

h | |||||||||||

|

uibh |

i:w |

uic |

ʊ |

uid |

wɪd |

h | |||||||||||

|

adh |

ɑː |

agh |

ɑː |

al |

ɑ |

alh |

ɑʎ |

am |

ɑm |

h | |||||||

|

ædh |

æː |

ægh |

æː |

æl |

æl |

ælh |

æj |

æm |

æm |

ɬ | |||||||

|

aidh |

iː |

ɮ |

aigh |

iː |

ɮ |

ail |

ɪl |

ailh |

ij |

aim |

ɪm |

ɬ | |||||

|

aodh |

ɔː |

aogh |

ɔː |

aol |

ɔl |

aolh |

ɔʎ |

aom |

ɔm |

h | |||||||

|

aough |

aːw |

h | |||||||||||||||

|

audh |

ɑː |

augh |

ʊː |

aul |

ʊl |

aulh |

ʊʎ |

aum |

ɒm |

h | |||||||

|

edh |

ɪð |

egh |

ø |

el |

ɛl |

elh |

ɛj |

em |

ɛm |

ɬ | |||||||

|

eadh |

ɪːð |

eagh |

ɑː |

eal |

ɑl |

ealh |

ɑː.j |

eam |

ɑm |

h | |||||||

|

eaidh |

iːð |

eaigh |

iː |

eail |

iːl |

eailh |

iːj |

eaim |

iːm |

ɮ | |||||||

|

eidh |

iː |

eigh |

iː |

ɮ |

eil |

il |

eilh |

ɛʎ |

eim |

ɛm |

ɬ | ||||||

|

eodh |

œːð |

eogh |

œː |

eol |

ʏl |

eom |

ʏm |

ɬ | |||||||||

|

eoidh |

iːð |

eoigh |

iː |

eoil |

iːl |

eoilh |

iːj |

eoim |

iːm |

ɮ | |||||||

|

idh |

ɪː |

igh |

i |

il |

ɪl |

ilh |

ɪʎ |

im |

ɪm |

ɬ | |||||||

|

iadh |

ɛː |

iagh |

ia |

ial |

jɑl |

ialh |

iːʎ |

ɮ |

iam |

ɛːm |

ɬ | ||||||

|

iaidh |

iː |

iaigh |

iː |

iail |

iːl |

iailh |

iːj |

iaim |

iːm |

ɮ | |||||||

|

iedh |

ijɛː |

ol |

ɒl |

om |

ɐm |

ɬ | |||||||||||

|

ieidh |

iː |

ieigh |

iː |

ɮ | |||||||||||||

|

iodh |

ijɔː |

ɬ | |||||||||||||||

|

odh |

ɒ |

ogh |

ɒ |

ɬ | |||||||||||||

|

oadh |

ʋɑː |

oagh |

ɒː |

oal |

ʋɑl |

oalh |

wɑʎ |

oam |

wɑm |

- | |||||||

|

oaidh |

wɛː |

oaigh |

iː |

oail |

iːl |

oailh |

iːj |

oaim |

iːm |

ɮ | |||||||

|

œdh |

ɛː |

oegh |

œː |

œl |

œl |

œlh |

œːj |

œm |

œm |

ɬ | |||||||

|

oidh |

iː |

oigh |

iː |

oil |

iːl |

oilh |

iːj |

oim |

iːm |

ɮ | |||||||

| ough | u | ɬ | |||||||||||||||

|

udh |

ʊː |

ɬ | |||||||||||||||

|

uadh |

wɑː |

uagh |

wɑ |

ual |

wɑl |

uam |

əm |

h | |||||||||

|

uaidh |

yː |

uaigh |

wiː |

uail |

wiːl |

uaim |

yːm |

- | |||||||||

|

uedh |

wɛː |

uegh |

wɛ |

uel |

wɛl |

uelh |

wɛj |

- | |||||||||

|

uidh |

wiː |

uigh |

wiː |

uil |

wil |

uilh |

wiː |

- | |||||||||

|

amh |

ɑʋ |

an |

ɑn |

anh |

ɑŋ |

aph |

ɑf |

ar |

ɑʁ |

h | |||||||

|

æmh |

æw |

æn |

æn |

ænh |

æŋ |

ær |

æ |

ɬ | |||||||||

|

aimh |

ɪw |

ain |

ɪn |

ainh |

ĩː |

air |

ɛːɹ |

ɬ | |||||||||

|

aomh |

ʏːw |

aon |

ʏːn |

aonh |

ɒŋ |

aor |

ɒʁ |

ɬ | |||||||||

|

aumh |

ɒʋ |

aun |

ɒn |

aunh |

ʊŋ |

aur |

ʊʁ |

ɬ | |||||||||

|

emh |

ɛw |

en |

ɛn |

enh |

øŋ |

eph |

ɛf |

er |

əɹ |

h | |||||||

|

eamh |

ʏw |

ean |

ʏn |

eanh |

ɛŋ |

eaph |

ʏɸ |

ear |

ɪːəɹ |

ɬ | |||||||

|

eaimh |

iːw |

eain |

iːn |

eainh |

ĩː |

eaiph |

iːɸ |

eair |

ɪːɹ |

ɮ | |||||||

|

eimh |

ɛw |

ein |

ɛn |

einh |

ɛŋ |

eiph |

ɛːf |

eir |

iɹ |

ɬ | |||||||

|

eomh |

ʏw |

eon |

ʏn |

eonh |

œː |

eor |

iːɐɹ |

ɮ | ɬ | ||||||||

|

eoimh |

iːw |

eoin |

iːn |

eoinh |

ĩː |

eoiph |

iːɸ |

eoir |

iːɹ |

ɮ | |||||||

|

eum |

əʋ |

eun |

ən |

eunh |

əŋ |

ɬ | |||||||||||

|

imh |

ɪw |

in |

ɪn |

inh |

ɪŋ |

iph |

ɪf |

ir |

ɪɹ |

ɬ | |||||||

|

iamh |

ɛːw |

ian |

ɛːn |

ianh |

ĩː |

iaph |

ɛːf |

iar |

iɐɹ |

ɬ | |||||||

|

iaimh |

iːw |

iain |

iːn |

iainh |

ĩː |

ɬ |

iaiph |

iːɸ |

iair |

iːɹ |

ɮ | ||||||

|

omh |

ɒʋ |

on |

ɒn |

onh |

õ |

oph |

ɒf |

or |

ɒɹ |

h | |||||||

|

oamh |

ɑːʋ |

oan |

ɑːn |

h | |||||||||||||

|

oanh |

ʋɑŋ |

oar |

ʋʌʁ |

- | |||||||||||||

|

oaimh |

ʏːw |

oain |

ʏːn |

oair |

iːɹ |

h | |||||||||||

| oainh | ʋɐ̃ | oaiph | wiːɸ | - | |||||||||||||

|

œmh |

œʋ |

œr |

œʁ |

ɬ | |||||||||||||

|

oimh |

iːw |

oiph |

iːɸ |

oir |

oɹ |

h | |||||||||||

|

ur |

ʏɹ |

ɬ | |||||||||||||||

|

uamh |

ʏʋ |

uaph |

ɑːf |

uar |

ɑːɹ |

h | |||||||||||

| uaimh | yːw | uainh | ɐ̃ | uaiph | yːɸ | uair | yːəɹ | h | |||||||||

|

uain |

yːn |

ɬ | |||||||||||||||

|

uenh |

wẽ |

uer |

wəɹ |

- | |||||||||||||

|

uimh |

iw |

uin |

in |

ɬ | |||||||||||||

|

uiph |

iɸ |

ɬ | |||||||||||||||

|

arh |

ɑːɹ |

as |

ɑʃ |

ash |

ɑ |

at |

ɑth |

ath |

ɑːθ |

ɬ | |||||||

|

ærh |

æːɹ |

æs |

æʃ |

æsh |

æ |

æt |

æth |

æth |

iːθ |

ætg |

ɪdʒ |

ɮ | |||||

|

airh |

iːɹ |

ais |

iːʃ |

aish |

ɛʃ |

ait |

ɛth |

aith |

iːθ |

aitg |

ɛdʒ |

ɮ | |||||

|

aorh |

oːʁ |

aos |

ɒʃ |

aosh |

ɒʃ |

aoth |

ɒθ |

aotg |

ɒdʒ |

h | |||||||

|

aurh |

ʊːʁ |

aus |

aʃ |

aush |

ɔːʃ |

auth |

ɔːθ |

h | |||||||||

|

erh |

ɪʒ |

es |

ɪʃ |

esh |

ɪʃ |

et |

eth |

eth |

ɪθ |

etg |

ɪdʒ |

ɮ | |||||

|

earh |

ʏʁ |

eas |

ɪːʃ |

eash |

ɪːʃ |

eat |

ɛːth |

eath |

ɛːθ |

ɮ | |||||||

|

eairh |

iːʒ |

eais |

iːʃ |

eaish |

iːʃ |

eait |

iːth |

eaith |

iːθ |

eaitg |

iːdʒ |

ɮ | |||||

|

eirh |

iːʒ |

eis |

iːʃ |

eish |

iʃ |

eith |

iθ |

eitg |

idʒ |

ɮ | |||||||

|

eorh |

iːʒ |

eosh |

øʃ |

eoth |

øθ |

eotg |

ødʒ |

ɮ | |||||||||

|

eoirh |

iː |

eois |

iːʃ |

eoish |

iːʃ |

eoith |

iːθ |

eoitg |

iːdʒ |

ɮ | |||||||

|

eush |

œʃ |

euth |

œθ |

ɮ | |||||||||||||

|

irh |

ɪʒ |

is |

ɪʃ |

ish |

iʃ |

ith |

iθ |

itg |

idʒ |

ɮ | |||||||

|

iarh |

iːʒ |

ias |

iːʃ |

iash |

ɛːʃ |

iath |

ɛːθ |

iatg |

iːdʒ |

ɮ | |||||||

|

iairh |

iːʒ |

iais |

iːʃ |

iaish |

iːʃ |

iaith |

iːθ |

iaitg |

iːdʒ |

ɮ | |||||||

|

orh |

ɒʁ |

os |

ʌs |

osh |

oʃ |

oth |

ʌθ |

h | |||||||||

|

oarh |

ʋʒ |

oas |

ʋʌs |

oash |

wɐʃ |

oath |

wɐθ |

- | |||||||||

|

oairh |

wiːʒ |

oais |

iːʃ |

oaish |

wiːʃ |

oaith |

wiːθ |

oaitg |

wiːdʒ |

- | |||||||

|

œrh |

œʒ |

œsh |

ʌʃ |

œth |

œθ |

h | |||||||||||

|

oirh |

iːʒ |

ois |

iːʃ |

oish |

iːʃ |

oith |

iθ |

oitg |

idʒ |

ɮ | |||||||

|

urh |

ʊʒ |

ush |

ʊʃ |

uth |

ʊθ |

ɬ | |||||||||||

|

uarh |

ɑːʁ |

ɬ | |||||||||||||||

|

uash |

wɐʃ |

uath |

wɐθ |

- | |||||||||||||

|

uairh |

yːʒ |

uais |

yːʃ |

uaish |

wiːʃ |

uait |

ʋiːth |

uaith |

wiːθ |

uaitg |

wiːdʒ |

- | |||||

|

uerh |

wəʒ |

ues |

wəʃ |

uesh |

wɛʃ |

ueth |

wɪθ |

- | |||||||||

|

uirh |

iːʒ |

uis |

iːʃ |

uish |

iːʃ |

uith |

iːθ |

uitg |

iːdʒ |

ɮ |

Table 3[]

Vowels modifying precedent consonants.

|

Front |

Near-front |

Central |

Near-back |

Back | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Close |

i y |

u | |||

|

Near-close |

ɪ ʏ |

ʊ |

|||

|

Close-mid |

e ø |

ɘ |

o | ||

|

Mid |

ə |

||||

|

Open-mid |

ɛ œ |

ʌ ɔ | |||

|

Near-open |

æ |

ɐ |

|||

|

Open |

a |

ɑ ɒ |

Table 4[]

Modification of consonants.

|

original |

modified | |

|---|---|---|

|

b |

b |

v ʋ w |

|

c |

- ɬ h |

ɮ |

|

d |

d |

ð ʒ |

|

g |

ɦ |

dʒ |

|

l |

l |

w |

|

m |

m |

v ʋ |

|

n |

n |

ɲ |

|

p |

p |

f ɸ |

|

r |

r |

ɾʒ |

|

s |

s |

ʃ |

|

t |

t |

tʃ |

Grammar[]

| Gender | Cases | Numbers | Tenses | Persons | Moods | Voices | Aspects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verb | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nouns | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Adjectives | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Numbers | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Participles | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adverb | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Pronouns | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Adpositions | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Article | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Particle | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

First Reader[]

In the twentieth century, something like McGuffey's First Reader has been published:

The Borchennymendi texts appeared in the traditional alphabeth. ß is the sign for h; the sharp s takes the place of the normal s within or at the outset of a syllable and h is written with a decorative curl at is tail at the end of a word.

The words generally are of considerable length, because Borchennymendi is an agglutinative language, although it has some flexions.

Read aloud, this text sounds like:

Parts of speech[]

Words are divided into four parts of speech: substantives, verbs, adverbs and interjections.

- A substantive is a part of speech inflected for number and case, signifying a concrete or abstract entity.

- A verb is a part of speech without case inflection, but inflected for at least tense, person and number, signifying an activity or process performed or undergone. An adjective is any qualifier of a noun, without case, tense, person or number inflection. It is disputable whether verbs are inflected adjectives of adjectives are verbs without inflections. A participle is a part of speech, derived from a verb (or an adjective), sharing the features of the verb, the adverb and/or the noun. There are no equivalents for the common English verbs ‘to be’ and ‘to have’.

- An adverb is a part of speech without inflection, in modification of or in addition to a verb, adjective, clause, sentence, or other adverb

- An interjection is a part of speech expressing emotion alone. Borchennymendi is unfamiliar with expressions for ‘yes’ and ‘no’. The answer to a question and the confirmation or denial of a statement are formulated by resuming the principal verb in the preceding question or statement.

In Indo-European languages a pronoun is a part of speech substitutable for a noun and marked for a person. Borchennymendi pronouns are always pronominal suffixes and never stand alone.

The Borchennymendi language does not allow any prepositions.

Conjunctions[]

A conjunction binds together the discourse and filling gaps in its interpretation. It is always a prefix or an affix to some part of speech.

Operators[]

The primary conjunctions between two or more verbal constructions are not separate words, like the English ‘and’, ‘or’, ‘but’ etc. They are expressed by conjunctive suffixes, which may be added to verbs and, to a certain extent, also to substantives. William Bidewell in his 18th century grammar book did not call them ‘conjunctions’ but ‘operators’, as to avoid any confusion with the specific operator he called ‘conjunction’. The five operators in the primary class are:

|

Conjunction |

and |

-agh |

|

Disjunction |

or |

-eir; -eirtg |

|

Opposition |

but |

-bhuir |

|

Implication |

when ...then |

-eish |

|

Condition |

if and only if … then |

-eith |

Conjunction according to the Bidewell terminology is performed by the suffix -agh. It corresponds to the English ‘and’:

pamhnhe rhaetgidh: chapheaidhnhe saeighuithidhagh: I eat some bread and I drink some coffee.

(The suffix -nhe is that of the partitive case. The absolutive case would imply that the bread would not change its appearance be being consumed and the resultative case cannot be used because it would mean that I have eaten all of the bread.)

The disjunctive operator is -eir:

pamhnhe rhaetgidh: chapheaidhnhe saeighuithidheir: I eat some bread or I drink some coffee.

The two possibilities mentioned do not necessarily exclude each other. The sentence may mean that no real choice between bread and coffee is made: having both of them at one and the same occasion is still possible.

When this exclusion has to be expressed the suffix -eirtg must be added:

pamhnhe rhaetgidh: chapheaidhnhe saeighuithidheirtg: Either I eat some bread or I drink some coffee, but never at the same time.

In the sentence: pamhnhe rhaetgidh: chapheaidhnhe saeighuithidhbhuir: I eat some bread but I drink some coffee, an opposition of the verbal clauses and the nouns is achieved: bread, being food, is eaten but coffee is drunk as it is a beverage.

There are two conditional operators, which correspond to ‘if’ (or ‘when’) and to ‘if and only if’. In: pamhnhe rhaetgidheish: chapheaidhnhe saeighuithidh: When I eat some bread, I drink some coffee, the operator suffix for the sufficient condition is -eish, while the suffix for the necessary condition or conditio sine qua non is: -eith: pamhnhe rhaetgidheith: chapheaidhnhe saeighuithidh: If I eat some bread, then and only then I drink some coffee. In conditional clauses like these, the suffixes must be added to the part in which the fulfillment of the condition is stated, not to that in which the condition itself is mentioned. The precise distinction between the suffixes -eish and -eith is of great importance, since -eith always expresses a necessary condition. A flight attendant saying ‘(When we land at Bojarochne Airport, please) remain seated …” (aithoaghredhmuicechoareighemeish) is making a standard announcement. If ‘remain seated’ would be: aithoaghredhmuicechoareighemeith, the communication would imply: “If we land …”, which probably would have a disquieting effect on the passengers.

All these operator suffixes can be added to both verbs and nouns:

pamhnhe chapheaidhnheagh: Bread and coffee (for a breakfast).

tathnhe chapheaidhnheir: Tea or coffee (are served at breakfast).

tathnhe chapheaidhnheirtg: Either tea or coffee; not both of them.

pamhnhe chapheaidhnhebhuir: I would like some bread, but also a cup of coffee.

pamhnhe chapheaidhnheish: Having some bread means: always a cup of coffee to go with it.

pamhnhe chapheaidhnheith: No coffee without bread; no bread without coffee.

Adjunct[]

The general modifier da- as a prefix to a verb/adjective adds a property to a noun.In some respects, is is an operator, for its basic meaning is: 'of which is true: ...' The Borchennymendi allows the addition of only one adjective to a radix, e.g.: chaseth - a house (ergative case), chasmaugheth - a big house. For the expression 'a large green house' there are three possibilities. The first is an attributive adjunct introduced by the affix da- to the radix nusaigheachthaun: chasmaugheth danusaigheachthauneth: (ergative case for both the subject of the sentence and for its attributive adjunct) has a restrictive meaning: the big house, that is green, would imply that there are more big houses than the green one, but only the green house is occupied by the the person one is looking for. The second possibility chasmaugheth danusaigheachthechathes: (an adverbial adjunct expressing an extension: the large house, of which is true that it is green at this moment, has been green in the past and is likely to stay green in the future) is a verbal construction, because the radix nusaigheachthaun is regarded as the verb: 'to be green'. The meaning of this clause is: the big house which is green. Aspects may be added to the verb, which is not allowed in the attributive adjunt. The big house which is now being painted green would be: chasmaugeth danusaigheachtroananes: it begins (the inchoative aspect) te be green right now (-an is for the common present), the expected result being nondescript or altogether irrelevant. A restriction in an attributive adjunct is the third possibility: the big house that is green could also be: chasmaugheth: danusaigheachthmaith: with the punctuation mark after each of the words and the adjunct in the adverbial case. A clause like this may mean: the big house, whose only characteristic is its green colour.

Verbs[]

Gender

There is no grammatical gender, neither in nominal, nor in verbal constructions. In the second and third persons of the verbal conjugation, a distinction is made between concrete and abstract categories. This will be explained in the section dealing with nouns.

Number

Borchennymendi involves a three-way number contrast between singular, dual and plural.

In the sentence: The apple is fresh - almhaen paertearotganes:the subject almha- takes the suffix of the nominative -en, because paertearotg-, denoting both the adjective ‘fresh’ and the verb ‘to be fresh’, is in this case considered to be an intransitive verb. Two suffixes have to be attached to the radix: -an- for the common present and -es for the third person singular for concrete items.

In: The apples are fresh - almhaemen paertearotganeshem: the suffix -em for the plural number appears twice: in the penultimate position of almhaemen and as the final suffix of the verbal construction, as the grammatical number is an agreement category. The distinction between abstract and concrete nouns is a category of the same type. The two apples are fresh - almhasoidhnen paertearotganeshough: In the dual, nouns normally are classified by -soidhn, whereas the verbtakes the suffix -ough. The plural classifier is -em for the noun as well as for the verb. Some nouns form their dual through apophony or phonetic modification: two - steidhm four (two times two) - staedhm. This type of nouns may appear in a second dual form: staedhmsoidhn (2 x 2 x 2) - eight.

The dual of almha is formed in the normal way, but

sechoedhr, a lady’s shoe, shows apophony in the dual: seachadhr.

sechoedhren uibhshetloeianes: - The shoe is black;

seachadhren uibhshetloeianeshough: - The pair of shoes is black.

‘Two pairs of shoes’, seachadhsoidhn, make up four shoes, so that the double dual for the noun requires a plural form in the verb:

seachadhsoidhn uibhshetloeianeshem:

and not: seachadhsoidhn uibhshetloeianeshough:

A collective noun is a word that designates a group of objects or beings regarded as a whole, such as "flock", "team", or "corporation". In Borchennymendi, just as in English, they may be interpreted as plural or incidentally when their meaning is that of a couple consisting of two items, persons or concepts (e.g. auth - ‘a pair’, aidhreguige - ‘a married couple’, aothmeraidh ‘duality, ambiguity’) as dual, which affects the conjugation of the verb according to the above mentioned rules. In Borchennymendi, phrases such as ‘The committee are meeting’ are even more common than in British English. The so-called agreement in sensu (i.e. with the meaning of a noun, rather than with its form) is highly favoured. This type of construction varies with the level of formality.

Person[]

For verbal constructions, six persons are distinguished:

|

singular |

dual |

plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

I |

incl. |

you (sg.) and I |

incl. |

you (pl.) and I |

|

excl. |

he/she and I |

excl. |

they and I | ||

|

2. concr. |

you |

both of you |

you (pl.) | ||

|

2. abstr. |

id. |

id. |

id. | ||

|

3. concr |

he, she |

both of them |

they | ||

|

3. abstr. |

it |

both of them |

they | ||

|

4. |

someone, something |

two persons, two things |

people, things | ||

|

5. |

everyone, everything |

both, both things |

all of them | ||

|

6. |

no one, nothing |

none of both |

none of them | ||

Gender being no category in Borchennymendi, there are no distinct suffixes for 'he', 'she' and 'it' for animate creatures.In the second and third persons concrete and abstract agents of the verb require different sufiixes. Concrete are really existing persons, animate and inanimate objects. Abstract are all the others. The categories, however, are interchangeble to a certain extent. omenh as a concrete noun means 'a human being', so it takes the third person concrete in a verbal construction of which it is the subject. As an abstract noun it means 'mankind', so its suffix will be that of the third person abstract.

Originally concrete animals or items that have existed but have ceased to do so are regarded as belonging to the abstract category. This semantic shift affects the choice between the two possibilities in the second and third person.

The apple is fresh - almhaen paertearotganes:

implies that the fresh apple is still present. About a stolen or consumed apple that has been fresh one should say:

almhaen paertearotgechaithesth:

while

almhaen paertearotgechaithes:

would imply that the apple is still there and once had been fresh, but now has lost its original quality.

Prudence is called for when adding the suffixes -adh (2sg. abstr.), -esth (3sg. abstr.), -adhough, -esthough (dual.), -adhem or -esthem (plur.) to a verbal radix if a person is the subject. Very often it implies pejorative appellations. It is not customary to speak about deceased persons as if they were abstract notions, not even when their demise happened centuries ago. Such usage would express a considerable doubt about their historicity. 'Saint Nicolas' as a 4th century bishop, although he might be somewhat legendary, is concrete, but 'Santa Claus' safely may be regarded as an abstract noun by those who do not believe in his real existence. (Mind the children!) In the context of litterary fiction the names and designations of non-historical personalities are treated as concrete nouns. Fairies, gnomes etc.are abstract; angels are so for non-believers, but religious people regard them as concrete beings. When a living person is the subject, special precautions must be taken in the third person singular of the spoken language, as in practically all instances the difference between abstraction and concreteness is indicated merely by the stressed syllable: 'he/she is afraid' - uidhranes - ˈʌɹɐnɛʃ; 'it (abstr.) is afraid' - uidhranesth - ʌɹɐˈnɛʃ. The use of the abstract form for living people shows undisguised contempt. A concrete woman is a lady, an abstract one is a tramp.

The fourth person refers to a nondescript member of a class. The fifth includes all members of that class, while the sixth indicates that the class is void.

The suffixes, placed at the end of the entire verbal construction, are:

|

singular |

dual |

plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

-idh |

incl. |

-idhough |

incl. |

-idhem |

|

excl. |

-arhough |

excl. |

-arhem | ||

|

2. concr. |

-eigh |

-eighough |

-eighem | ||

|

2. abstr. |

-adh |

-adhough |

-adhem | ||

|

3. concr |

-es |

-eshough |

-eshem | ||

|

3. abstr. |

-esth |

-esthough |

-esthem | ||

|

4. |

-ain |

-ainough |

-ainem | ||

|

5. |

-elhe |

-elhough |

-elhem | ||

|

6. |

-melhe |

-melhough |

-melhem | ||

Function[]

The functional suffix is the first to be added to the verbal stem, called radix. There are four of these functions:

- indicative, with no mark;

- negative marked by -me;

- affirmative, with to possible suffixes:

- -es

when the answer to a question is affirmative: 'Is this a tree? Yes, it is.' Borchennymendi has no equivalents for 'yes' and 'no'. When replying to a question, the verb is repeated with the affirmative suffix.If the answer would be of the type: 'Is this a tree? No, it is a plant.', the suffix:

- -iointegh

has to be attached to the radix in the first possible position, which is, generally (though there are exceptions) the one immediately after.

The interrogative function is reached by adding

- -riaidh

to the radix.

Voice[]

There are five voices:

active, unmarked;

middle, with the suffix:

- -moigh,

indicating that the action or experience is to the benefit of the agens;

reflexive,

- -er;

reciprocal, with the suffix

- -epher.

The reciprocal mood presupposes a dual or plural subject or a subject formally in singular, but semantically plural, like as 'people, class, cattle, police etc.'.

Mood

The ten moods are:

|

moods |

expression |

example | ||

|

- |

indicative |

fact |

I walk | |

|

-agh |

conjunctive |

I |

supplemental verb |

and I walk |

|

-tagh |

II |

coincidence |

while I walk | |

|

-siaidh |

subjunctive |

I |

condition |

if I walk; when I walk |

|

-chuiaidh |

II |

reason |

as I walk | |

|

-peraidh |

III |

cause |

because I walk | |

|

-medhraidh |

IV |

contradistinction |

although I walk | |

| -midhraidh | lest I walk | |||

|

-ghedhraidh |

V |

consequence |

so that I walk | |

|

-raedh |

optative |

desirability |

in order that I walk | |

|

may I walk! |

The first conjunctive mood is nothing more than a simple conjunction of two coordinate verbal constructions. As a rule, its suffix does not follow the radix, but finds itself at the end of an entire construction.

Tense

The next position in a verbal construct is taken by one of the fourteen tenses, if they are applicable:

The terms given in the second column of the table do not cover those of e.g. the Latin grammar. Tenses are defined by three criteria: the time when the action commences, the moment on which it takes place, and that on which it is or is likely to be terminated.

|

suffix |

tense |

outset |

moment |

end |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

- |

simple present |

indefinite |

present |

indefinite |

|

-anaiph |

momentaneous present |

present |

present |

present |

|

-an |

common present |

past |

present |

indefinite |

|

-echain |

aorist |

past |

past |

indefinite |

|

-echath |

imperfect |

past |

past |

without result |

|

-echaith |

perfect |

past |

past |

with result |

|

-redh |

future |

present or past |

future |

indefinite |

|

-redhath |

future imperfect |

present or past |

future |

without expected result |

|

-redaith |

future perfect |

present or past |

future |

with expected result |

|

-than |

conditional present |

indefinite |

present |

unsatisfied condition |

|

-thoun |

conditional aorist |

past |

past |

unsatisfied condition |

|

-ghedh |

conditional perfect |

past |

past |

satisfied condition |

|

-thedh |

conditional future |

present or past |

future |

satisfied condition |

Examples of their use are:

|

tense |

example clauses |

|---|---|

|

simple present |

I’m just walking around. |

|

momentaneous present |

I fall down. |

|

common present |

I walk. |

|

aorist |

Suddenly I fell down the stairs. |

|

imperfect |

I walked but I couldn’t find her house. |

|

perfect |

I walked a while and I found the house. |

|

future |

I shall walk. |

|

future imperfect |

I’ll have to stay forever. |

|

future perfect |

I’ll take look. |

|

conditional present |

I walk till a have found her house. |

|

conditional aorist |

I walked to see if I could find her house. |

|

conditional perfect |

I walked till I had found her house. |

|

conditional future |

I shall keep walking till I have found her house. |

Aspect[]

The verbal aspects are quite numerous. Integration of a complete verbal radix in the penultimate position of a construction is possible. It would result in a more refined aspect than the abbreviated radices give. Aspects given by truncated radices are:

Initial aspects:

|

-sea |

counterfactual potential |

I can, but I don’t. |

|

-sear |

potential |

I’m capable and willing. |

|

-bu |

counterfactual voluntative |

I want to do it, but I can’t. |

|

-bur |

voluntative |

I want to do it, and I will. |

|

-cron |

deontic |

I’m allowed to take measures. |

|

-odhr |

imperative |

You have to do your duties. |

|

-ain |

optative |

May it be for ever! |

|

-eirn |

sperative |

I hope to be an officer. |

|

-loa |

dubitative |

Perhaps I’ll be promoted. |

|

-loagh |

eventive |

I expect to be promoted in the next year. |

|

-baith |

momentaneous |

I go home as soon as it is finished. |

|

-airth |

prospective |

I am about to begin. |

|

-roa |

inchoative |

I start working. |

|

-eatg |

conative |

I try to cook a meal. |

Progressive aspects:

|

-sin |

progressive |

I’m washing the dishes. |

|

-singheoth |

stative |

I’m doing my homework, but it is not finished yet. |

|

-coin |

continuous |

I keep doing efforts. |

|

-coingeth |

iterative |

I have read ‘The Lord of the Rings’ several times. |

|

-coinrand |

frequentative |

I explain it repeatedly. |

|

-siadh |

generic |

I always wear a blue jacket. |

|

-siadher |

habitual |

I wash may car every Saturday. |

Intentional aspects:

|

-aodh |

intentional |

The charlady cleans up every corner in our house. |

|

-taemhaodh |

perfective |

She cleans up the whole of it. |

|

-taim |

accidental |

Accidentally, she has broken a window. |

|

-liad |

interruptive |

Every now and then she takes a break. |

|

-liadhrant |

parcitive |

My husband incidentally shares in the cleaning up. |

|

-muicech |

delimitative |

We have been cleaning up for several hours. |

|

-muicechor |

defective |

I’m cleaning up for half an hour and then I return to write. |

|

-muicechoar |

durative |

I’m cleaning up till three o’clock. |

Retrospective aspects:

|

-tug |

terminative |

I have finished my homework. |

|

-tuig |

cessative |

I stopped doing my homework, finished or not. |

|

-tuigor |

pausative |

I stopped doing it for half an hour. |

|

-tugh |

resumptive |

I’ve done it again. |

Jussive aspects:

|

-gitg |

connivitive |

I tolerate someone to steal my horse. |

|

-ghais |

desiderative |

I wish she would come. |

|

-ghaior |

jussive |

The sergeant ordered the soldiers to march. |

|

-ghaiorin |

permissive |

I admit my neighbours to sit down in my backyard. |

|

-lein |

admonitive |

I advise them to do so. |

|

-leinoar |

exhortative |

I even prompt them to have fun in the garden. |

Cogitative aspects:

|

-nea |

cogitative |

I think it is true. |

|

-neath |

creditive |

I believe it is true. |

|

-neathoin |

apparitive |

He looks like a wealthy man. |

|

-bhatg |

similative |

He seems to be wealthy. |

|

-thuirdg |

evenitive |

He appears to be wealthy. |

|

-ci |

conclusive |

He draws the conclusion that he is wealthy. |

|

-cit |

evidential |

It’s obvious that he is wealthy. |

|

-loch |

mentitive |

He lies about his wealth. |

Nominalisation[]

Adjectives can be treated as intransitive verbs without the verb itself being nominalised. The sentences: ‘It is a house. The house is white.’ are verbal constructions:

chasanes: chasen chaindidhanes: (litt.: "It houses. The house whites.")

|

chas - |

-an |

-es |

|

radix |

common present tense |

3d person sing. concr. |

|

chas - |

-en |

|

|

radix |

nominative case |

|

|

chaindidh - |

- an |

- es |

|

radix |

common present tense |

3d person sing. concr. |

Conjugated verbs are transformed to nouns in five different ways:

|

-uin |

gerund |

verb to |

substantive |

the opening |

|

-der |

infinitive |

verb to |

adverb |

easy to understand |

|

-natg |

participle |

verb to |

noun (substantive or adjective) |

Let sleeping dogs lie. |

|

-menduigh |

gerundive |

verb to |

noun (substantive or adjective) |

a readable book |

|

-urh |

supine |

verb to |

adverb |

(I have come ) to take it with me. |

Nouns[]

Singular

The singular form of a noun remains unmarked.

Dual

The dual is normally formed by adding the suffix -soidhn to the radix.

Twenty-nine radices have irregular dual forms:

|

chuidhnalh |

three |

chudhnalh |

six |

|

citla |

turn, occasion |

caetle |

|

|

coirne |

horn, conch |

caerne |

|

|

cuth |

hand (obsolete) |

choith |

|

|

deoch |

part, share |

daich |

|

|

eochaildh |

eye |

eachaeldh |

|

|

ertg |

seven |

aertg |

fourteen |

|

gaecheshaen |

lip |

guicheshin |

|

|

gloir |

arm |

glaer |

|

|

idanach |

leg |

doinecheadh |

|

|

lamhthaith |

basket |

liamtheth |

|

|

leaoith |

chair |

leithe |

|

|

leintg |

twenty |

lantg |

forty |

|

madan |

wall |

maeduin |

|

|

maircheth |

stick |

merchaith |

|

|

manh |

hand |

mainh |

|

|

mhointe |

mountain |

mhuinte |

|

|

omenh |

human being |

oamainh |

plural: oamenh |

|

phauthi |

foot |

phaeth |

|

|

pheigoart |

doorpost |

phagart |

|

|

sechoedhr |

shoe |

seachadhr |

(of a woman) |

|

shaipuith |

shoe |

shapath |

(of a man) |

|

sheith |

fish |

shath |

|

|

siulaim |

kidney |

sialam |

|

|

steidhm |

two |

staedhm |

four |

|

taisteal |

cheek |

togtailhae |

|

|

tlachtga |

ship |

tluicht |

|

|

tledhl |

five |

tlaedhl |

ten |

|

tunui |

son |

tanae |

Fifteen dual forms indicate semantic shifts:

|

achran |

season |

ichrain |

summer and winter |

|

ainidhmadh |

heart |

ainidhmaedh |

intimacy |

|

aodhghin |

fist |

edhghin |

combat |

|

bhairheitg |

chest |

bharhatg |

household goods |

|

buartha |

bed (obsolete) |

beirth |

double bed |

|

comhghan |

coin |

coimhghain |

a piece of 14 or 36 pence |

|

diamh |

day |

diaumh |

twenty-four hours |

|

gochtaomh |

tooth |

geichtamh |

set of dentures |

|

indrechtach |

bed |

indrachteich |

double room in a hotel |

|

mhaetloetg |

finger |

mhatlotg |

thumb and index finger |

|

rhotathrain |

wheel |

rhoetathrin |

bicycle (in literary language) |

|

saeighuith |

beverage |

sagath |

wine and water |

|

shaerhphein |

claw |

sharphin |

calamity, doom |

|

teichndopoi |

jaw |

tachndeiph |

lower and upper jaw |

|

thelhsuntitg |

bedsheet |

thalsunteitg |

bedclothes |

In the singular of these words the first syllable is stressed; in the dual it is the final one that bears the stress, except comhghan - coimhghain: <ˈhɐvɘn> - <ˈɬɪːvɪn>. When the regular dual of these words is used the semantic shift will not occur: achransoidhn - two seasons, ainimadhsoidhn - two hearts, etc.

Several words without a dual form or even a strictly dual meaning will always cause the conjugation of the verb of which they are subjects according to the dual number:

|

aidhreguige |

a married couple |

|

aemhceithpheichaeth |

health |

|

aeneaetg |

blessing |

|

aithnigh |

gorge, ravin |

|

aonach |

outline of a rectangle (not the circumference of a circle) |

|

aothmeraidh |

duality, ambiguity |

|

aunhrecuith |

fork |

|

auth |

a pair |

|

bandnoigha |

beak (of a bird) |

|

belh |

war, battle |

|

bhurhui |

abomination, disgust |

|

cairbre |

gate |

|

chodhstum |

suit, costume (of a man) |

|

daich |

catastrophe, disaster |

|

(daigh, accident is singular) | |

|

dhostaithe |

fate, destiny |

|

duiseacht |

hunger and thirst at the same time |

|

eaechloeirnabhaen |

prosperity |

|

eigeantach |

king and queen as a couple |

|

enelant |

England (not Great Britain) |

|

gaulhmai |

electric current |

|

geanelh |

window |

|

geotg |

street, avenue (in a city, not in a smaller town) |

|

ghaoitheacht |

coat |

|

ghlaeibhe |

sword |

|

ghuiari |

saw |

|

lermaeaitheath |

profit |

|

lhaeoectuitlbheishae |

anxiety |

|

lheinhlin |

gesture, bearing |

|

lhemotaibh |

interruption, breakdown |

|

lheothu |

quarrel, strife |

|

lhibaithinteanuin |

girdle, belt |

|

lhoatntaubhui |

debt |

|

lhuilhpheichpaeitg |

profit, earnings |

|

liath |

conflict |

|

luishraemh |

parents |

|

maodhg |

trousers |

|

mhaeceatu |

scissors |

|

mhaeiemaei |

size (of clothing and footwear) |

|

mhaethaetg |

wrinkle, furrow |

|

mhoebhaeoenphetg |

conspiracy |

|

mhorhtea |

danger, risk |

|

micheopaersoatg |

a pair of pincers |

|

muirhaeoetg |

dance |

|

nauntnhetrheitg |

regal, reed organ |

|

nhuithcuthbaeth |

frontier, boundary |

|

ocanhtaur |

outward appearance |

|

pheabgheolhaord |

pants, trousers |

|

phoishoir |

a two pound bank note |

|

raetamhphar |

a pair of tongues |

|

raoghsathau |

symbol |

|

shaeoechleaeshoei |

gun, rifle |

|

shaognhauntnethen |

problem, question |

|

shothluirhnhoatlon |

parliament |

|

taimiai |

damage |

|

teiaelhae |

person |

|

thotg |

incision |

|

thuindealbh |

character, quality |

|

tlaubnhabhoitg |

surprise |

|

tlaucai |

grief, regret |

|

tluinhmhuirghaurd |

war |

|

toiglethgoatg |

risk |

All these words have a regular dual form when two of these entities or concepts are referred to: teiaelhaesoidhn - two persons, tluinhmhuirghaurdsoidhn - the two World Wars, phoishoirsoidhn - two 2-pound notes etc.

The use of the dual with sheidhlinh, shilling (1/10 pound), arose from the revision of the monetary system in 1963, prior to which a shilling had the value of one twentieth part of a pound. The existing coins were not retracted, so that after the 1st of September of that year they doubled their value. Younger people, who have not experienced the revision, generally use the singular again.

Plural

The regular plural form of nouns is accomplished by adding -em to the radix.

Several radices, especially those ending with a vowel, form their plural in different ways:

|

singular |

plural |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-ae |

-ai |

tlinhpithae |

fine, penalty |

tlinphitai |

|

-ai |

-es |

triabhai |

form, shape |

triabhes |

|

-aolhe |

-ai |

phearhtaolhe |

catholic |

phearhtai |

|

-au |

-ai |

pheghau |

cloud |

pheghai |

|

-bhu |

-bher |

shaibhu |

rope |

shaibher |

|

-ei |

-eis |

thoecphei |

top |

thoecpheis |

|

-eau |

-as |

nilheau |

grandfather |

nilheas |

|

-eo |

-ei |

abhrimeo |

spear |

abhrimei |

|

-ghe |

-ghes |

soalghe |

ball |

soalghes |

|

-iath |

-ieth |

sciath |

science |

scieth |

|

-oi |

-ois |

lhoacaiphrhautoi |

miser |

lhoacaiphrhautois |

|

-ui |

-ais |

moilhui |

feather |

moilhais |

Irregular plural forms are:

|

chairdseir |

cherseres |

gaol |

|

cheimhshotrhunhaur |

thruidhmserais * |

heel |

|

cheonpauthaor |

chanpheidtair |

spade |

|

odhamnaith ** |

phroughmage |

cheese |

|

oephe |

aiphe |

side |

|

oiph |

oephe |

egg |

|

omhuiritg |

chualdhshuish |

chance |

|

orhphailen |

urphelen |

orphelin |

|

orhui |

aerhai |

coast, shore |

|

paemhbhoein |

paemhbhenes |

shepherd |

|

pelhath |

palhaith |

dish |

|

peorhath |

meidhrghenes |

oar |

|

pheichmoen |

sepuildhchre *** |

grave, tomb |

|

phoidhneth |

alhphenetes |

pin |

|

pochsaebh |

pauchsuibh |

nephew |

|

puirelhea |

parlhes |

calf |

|

rege **** |

eigeantuich |

king |

* thruidhmserui (sg.) is only found in a poetic context and is nowadays obsolete.

** odhamnaith is the material noun, whereas phroughmage means ‘pieces of cheese’.

*** sepuildhchre is often taken in the sense of ‘graveyard, cimetery'.

**** regei (pl.) only in: regeichuidhnalh, Three Kings, the name of a village near St Thegda EQ, which is regarded as a singular noun.

For the conjugation of verbs the following formally singular nouns are considered as plurals:

1. All substantives with a plural suffix or a plural declension.

2. The following substantives in a singular form with a plural meaning:

|

achmhain |

parish, municipality |

|

aeushmaeir |

hair dress, hair |

|

aibiocht |

fauna, animal life |

|

aighneash |

flora, vegetation |

|

bearhmhighr |

forest, wood |

|

chashnhanhaenh |

story |

|

chedhnymh |

ocean, sea |

|

chuidhnaelhdhioirdh |

the amount of one pound, one shilling and one penny L 1: s 1: d 1 |

|

coetsaeghribrhein |

crowd |

|

dhiainer |

money |

|

etachuinidh |

The United States of America |

|

geichoethneoetlhoeaeth |

worship, liturgy |

|

gheidhlimidh |

collection |

|

ghuibhlach |

bundle, bunch of flowers |

|

goitpaughaoth |

religion |

|

ighneacha |

passion |

|

lhaithoathlheithoatg |

church as an organisation |

|

liathdhearg |

flock |

|

mhaemoimtaubhtloth |

government |

|

mhaeoelhnethoeaer |

fleet |

|

noibhnaph |

building, edifice |

|

peleibh |

mob |

|

phaimbeoth |

tools, gear |

|

poliaish |

police |

|

tilheadh |

artillery |

|

tloeir |

human body |

|

tluililhae |

cattle |

|

uincoashshoir |

university |

3. The names of materials. If they are added the plural suffix or if they are declined as a plural their meaning is that of objects made or consisting or that material. Sometimes they undergo a semantic shift: phachoigh is silver, but phachoighem is cutlery, even if it is not manufactured of silver. Silver objects in general are boinhleiaithphachoighem. There are three exceptions to this rule:

|

cathaoir |

manure |

cathaoirem |

dung, filth (very pejorative) |

|

lhaipht |

milk |

lhaiphtem |

dairy combined with meat, forbidden by the ecclesiastical dietary laws, so: illicit nutriments |

|

oage |

gold |

oagei |

fortune, capital |

4. The names of Borchennymi’s twenty-three cantons.

5. The names of some cities and towns in and outside Borchennymi:

|

adghreoindheagh |

Aronde IR |

|

|

aithaurhei |

Aithayrhei DI |

The general noun aithaurhei, brook, however is singular. |

|

asthterdau |

Amsterdam |

Note: nuighasthterdau, New York, is singular. |

|

baethuidhrae |

Bathyrae PÆ |

The homonymous name of the river is singular. |

|

bluiaitheadhe |

Blytheadh BE |

|

|

bodhreaighrioichneadh |

Bojarochne ER |

|

|

loughndresh |

London |

|

|

maidhnhaghriaidh |

Mannaree DG |

|

|

muighdarh |

Mygda MN |

The names of equally qualified groups of people (not that of animals or objects) may appear in the singular form, but if the verb of which they are the subject is conjugated in the third person of the abstract plural, they take a collective plural meaning:

gheiaer - a carpenter - the carpenters guild, now the organisation of building contractors;

gheichluth - a prostitute - prostitution;

thaophuibintroith - minister - Cabinet, Council of Ministers, The Crown.

Case endings

General

For the contrast between the subject and the object of a sentence Borchennymendi uses five cases. Two of them, the ergative and the nominative, are for the subject, Two others, the absolutive and the resultative cases, are for the object. The fifth, the accusative, may indicate both the subject and the object, which implies that the meaning of the term ´accusative case´ is totally different from what it is in the Latin grammar. The sixth, a subject case called the pegative, is used only with an indirect subject.

The following pairs occur in the first class of core cases:

|

subject |

object |

subject complement |

indirect object |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. ergative case |

2. absolutive case |

7. dative case | |

|

1. ergative case |

5. accusative case |

7. dative case | |

|

1. ergative case |

3. resultative case |

7. dative case | |

|

5. accusative case |

3. resultative case |

7. dative case | |

|

4. nominative case |

3. resultative case |

||

|

6. pegative case |

7. dative case |

1. and 2.: Ergative and absolutive[]

For the subject of a transitive verb that describes an action or a perception the ergative case is used with the suffix -eth, if the voice of the verb is active, reflexive or reciprocal. In the reflexive and reciprocal voices the object is implicated in the verb itself. In the active voice the object takes the suffix of the absolutive case -am, unless it meets with a change that is the result or the consequence of the action:

omheth puirtgam bhidhanes: the man sees the boy.

If the verb is in the middle voice, the ergative case has a different form, -ethidh.

omhethidh puirtgam bhidhmoighanes: the man sees the boy ‘for himself’, may mean: only the man and no one else sees the boy.

In both of these instances, the pair of cases is that of the ergative and the absolutive, because the verb is transitive and the object undergoes no changes at all.

1. and 5.: Ergative and accusative[]

If the object is changed in some way, suffers from the action or ceases to be existent, the accusative is the appropriate case. It determinates the object by the suffix -ar.

The accusative case must not be used if the result of the action is mentioned.

omheth puirtgar braidhthanes: the man beats the boy, is a correct sentence but: omheth puirtgar braidhthanes: lhoughranghedhraidhanroanes: the man beats the boy so that he (i.e. the boy) begins to cry, is not. The boy’s crying is the result of the beating.

(A correct sentence would be: omheth puirtgar braidhthanes lhoughranghedhraidhanroanes, but this means: the man beats the boy so that he himself (i.e. the man) starts weeping. This is indicated by the omission of the punctuation mark in the middle of the sentence.)

1. and 3.: Ergative and resultative[]

The resultative case, -artg, takes the place of the accusative if the object experiences damage etc. and the character of this damage, or whatever it be, is specified in the same sentence. The correct rendering of the action of the cruel man spanking the weeping boy therefore is:

omheth puirtgartg braidhthanes: lhoughranghedhraidhanroanes:

A really abominable action like:

omheth puirtgnemhnainartg braidhthanes: the man beats the boy to death,

also requires the resultative case for the object, to the radix of which the verb-adjective -nemhnain- is added. omheth puirtgnemhnainar braidhthanes: would imply that the man is beating an already dead boy, because the action does not affect the state of the object.

The resultative case is never to be used for the object without a specification of the result.

5. and 3.: Accusative and resultative[]

One of the most remarkable features of Borchennymendi is the frequent use of the ‘constructio ad sententiam’.

The use of the passive voice of a verb implies that the patient of the action meets with damage or disadvantage. This requires the accusative -ar for the subject:

chasar mhaeigrhebhrothanes, the house is destroyed.

The passive voice, however, is normally avoided, because Borchennymendi has a fourth person for verbal constructions. Instead of this, one would rather say: chasar mhaeigrhebhanainem, ‘they’ devastate the house.

The accusativus pro ergativo appears with an intransitive verb in the active voice in the case that the mentioned performer of the action is in some way harmed or damaged.

ioghadhneth chasares mhaeigrhebhanes: John destroys his house, means that John ruins the house of some other person, while in: ioghadhnar chasartgeres mhaeigrhebhanes, John ravages his own property, and a ruined house is the result of what John is doing, so -artg-, the resultative, has to be added to the radix chas- before the pronominal suffix -eres, ‘his own’.

If John would have some advantage from the personal destruction of his dwelling, the middle voice has to be used for the verb, which causes the extended suffix -ethidh for the subject and the accusative for the object, because the result of the action is unmentioned: ioghadhnethidh chasareres mhaeigrhebhmoighanes:

If the affected object of a transitive verb is no longer existent as such after the action has been performed, the accusative suffix may be combined with that of the resultative case. In: chuistereagheth ghlhanluaidhartgar chuistereaghechaines, the butcher has slaughtered a cow, ghlanluiaidh- takes the suffix -artgar, because the cow as has ceased to be a living creature as a result of the butcher's work. When the furious in the foregoing paragraph destroys his own house to such an extent that nothing is left of it after his activities, the sentence 'John has destroyed his own house' becomes: ioghadhnar chasarartgeres mhaeigrhebhechatheres, with 'John' in the accusative and 'house' in the accusative-resultative case.

4. and 3.: Nominative and resultative[]

The subject of a nominal predicate takes the suffix of the nominative, -ur. The nominal complement, being the result of the predicate, is marked with that of the resultative -artg.

The nominative appears as the suffix for the subjects of the following verbs:

|

ceirenau |

to be surnamed |

|

eolaithe |

to become |

|

galaoireadh |

to be renamed as * |

|

genhshoichai |

to be famous as |

|

niamh |

to be called |

|

pelenaoth |

to be born as |

|

phaoth |

to seem |

|

thuirdgmeath |

to appear |

For instance: ioghadhnur moirgauthartg genhshoichaies: John is a famous teacher; ioghadhnur moirgauthartg eolaitheansingheothes: John is becoming a teacher (i.e. he is in a college of education) but has not yet taken his finals.

* galaoireadh- has a specific connotation: a person is renamed after he or she has been administered the extreme unction in case of mortal peril.

6. and 7.: Pegative and dative[]

The normal word order is SOV: subject, object, verb, as it in Latin (puer puellam amat, the boy loves the girl) and in many other natural languages. If the indirect object of a sentence has to be stressed, it is placed at the beginning of a clause: ioghadhneth chuadaicham mariadhimh aorhmirchanes: John gives a book to Mary,

mariadhimh ioghadhneinth chuadaicham aorhmirchanes: To Mary (and to no one else) John gives a book.

For such a subject ‘in the second place’ the Borchennymendi has a special case form, the pegative with the suffix -einth. It cannot appear without a preceding indirect object with a case ending from the dative class.

8. Translative[]

The direct object can also undergo a change to its advantage as the result of a performed action. For those instances, the Borchennymendi has a special case ending to indicate the positive result as an indirect object. In 'The rich man made John his heir', 'the rich man' has the ergative ending, 'John' the absolutive, and 'his heir' the translative -meth: taegnheisheth ioghadhnam emrhoeilhtlaelhoethmetheres tughmaeghechanes:

5. and 8.: Accusative and translative[]

The translative case may be combined with the suffix for the accusative if the object is damaged or harmed etc. and the result of the action is specified in an unambiguous way: moirgautheth lhethrear nheabrhoaghemarmeth ribhanes: the teacher tears the letter to shreds. Both the letter and the resulting shreds are considered as damaged, the result of tearing letters can only be some shreds, so: nheabrhoagh, pl. nheabrhoaghem, is suffixed:-armeth. If the teacher's interests are affected in a negative sense by tearing his own letter to pieces, this has to be translated as: moirgauthar lhethrearartgeres nheabrhoaghemarmeth ribhanes: 'teacher' = accusativus pro nominativo; 'letter'=accusative + resultative + 'his own'; 'shreds'=accusative + translative: three instances of the accusative case for the subject, the object and the indirect object!

4.and 8.: Nominative and translative[]

Only with the verb lhoich-, to become, the translative case has a different form: -colhin for persons and -colh for states, objects and entities. The subject of the sentence has the nominative ending. ioghadhnur moirgauthcolhin lhoichansines: John is becoming a teacher. The meaning of such a sentence is far more neutral than the already given example: ioghadhnur moirgauthartg eolaitheansingheothes:

9. Essive cases[]

The cases of the second class are verb-independent and make a statement about a quality of the noun to which their ending is attached. The modal essive has a neutral significance and offers no opinion about the reality of the quality it mentions. The suffixes are -pheidh for states, objects and entities, and -pheidhin for persons: teinhchiairpheidh: as an exception; moirgauthpheidhin: as a teacher, can be said about a person who is really a teacher just as well about someone who pretends to be one.

The essive case is used when the speaker has a reason to be convinced that the quality is really present. It has also a pair of suffixes: -thuirin for persons and -thuir for objects etc. The last form is often seen together with the gerund which transforms a verbal radix into a noun. So: moirgauthuirin (the duplication of -th- is not allowed!): in the undisputed quality of a teacher, but: moirgauthanesuinthuirin: in his or her quality of being in the position of a teacher.

The equative case, with the suffix pair -neathoidh / neathoidhin, is reserved for the denial of a quality or for the expression of a dubious quality: moirgauthneathoidhin may be said about someone who as if he or she were teacher, which this person is probably not.

The formal essive (-mentigh) and the adverbial case (-mi) both transform nouns into adverbs.He speaks fluently French: gaidhlementigh tlaesaeuthmi ruadhes:

10. Vocative case[]

The vocative is used for addressing a person or an entity with or without a preceding interjection. Its case ending -elaidh is the only instance where a pronominal affix precedes the suffix instead of following it. Only the affixes for the first person singular, plural exclusive and dual (exclusive) can be used to form:

idhelaidh - my …

arhoughelaidh - … of the two of us

arhemelaidh - our …

In Borchennymi, it is not customary to call anyone by his of her first or family name. The vocative ending, therefore, is never added to the name of a person. Only functions and kinship terms normally take the vocative ending when a person is directly spoken to. Not even a husband will ever call his wife Mary or Janet, nor vice versa.(They will prefer pet names instead ...) Little children never hear their names in the vocative. Already at their baptism the minister does not pronounce a formula such as: 'Maurice, I baptise you ...', but will say: 'The child Maurice is baptised...'

When introducing an unknown person, his or her function is always mentioned: Mrs X, attorney; Mr Y, father of seven children. Mrs X will be addressed to as: eoeblhuimhaidhelaidh, ‘my solicitor’, until the conversation will become informal (which point in Borchennymi is reached soon enough); from then she is: rhiadhaidhelaidh “my friend”. Mr Y, who might have retired or is unemployed, is: dalacharhemelaidh ‘our father’, till he becomes rhiadhaidhelaidh as well. Even the king is simply: regearhemelaidh, ‘our king’; not Your Majesty or whatever.